Process design, including its optimization and implementation, is a core discipline for Revenue Operations (RevOps). As the systems, structures, and tools that growth teams use become increasingly complex and interdependent, a robust approach to process improvement will be critical to eliminate friction. Less friction results in increased velocity.

Process design, including its optimization and implementation, is a core discipline for Revenue Operations (RevOps). As the systems, structures, and tools that growth teams use become increasingly complex and interdependent, a robust approach to process improvement will be critical to eliminate friction. Less friction results in increased velocity.

Over the last decade, we’ve worked on thousands of process improvement initiatives with more than 100 different teams. Here are the three most common and costly mistakes we see made, along with an easy-to-implement approach to ensuring you don’t make the same mistakes.

Jumping to the solution too soon

It’s human nature to start off seeking solutions. Most process improvements begin because someone is having a problem that’s negatively impacting multiple areas of performance and execution.

Jumping to a solution too soon is a mistake for three reasons:

- Without first clearly identifying and diagnosing the problem, you’re likely only going to be addressing a symptom of the problem.

- While the solution may mitigate the immediate problem, it will likely create greater latent friction and disruption within your structures.

- It multiplies the likelihood of miscommunication, which increases the possibility that you don’t solve any problem.

We recently experienced this in one of our Blue Team meetings. One of our advisors was working on a new HubSpot implementation, and our client was experiencing a problem in moving their processes over. Our advisor was seeking input from the team as to the best approach to solving the problem.

Not surprisingly, this led to a debate about which approach was best (or even if our approach to the solution was even valid). It wasn’t until someone interrupted the lively conversation by asking, “What’s the problem we’re trying to solve here?” that we realized that everyone involved in the discussion had perceived a different problem. Once we clearly defined the problem, the solution quickly became apparent.

Failure to address the business process first

The second mistake is a close cousin of the first and is increasingly common in sales and marketing operations. As technology becomes more embedded in everything we do, it has become easy to confuse technology with business processes.

Good process does two things:

- Enables

- Accelerates

It does this by creating clarity and alignment, and it reduces friction. Good process nudges behavior by making it easier for people to do those things that they should do.

This is why it’s crucial to clarify the underlying business processes influencing the problem/area to be improved and those that will likely be affected by the changes under consideration.

Using pronouns

The goal of excellent communication is not to be understood but rather to ensure that we are not misunderstood.

I forget who first told me about the dangers of pronouns, but since they shared this insight with me several years ago, I’ve seen just how commonplace, dangerous, and damaging pronouns are.

It’s easy to fall into the habit of using pronouns to describe things, and it leaves the situation open to too much interpretation. Here are two real-life examples of how pronouns wreak havoc on design:

- It’s not doing what it’s supposed to do.

- It needs to trigger an action for them so that they can keep track of where things are

Each pronoun refers to a different group of people or set of actions in both examples, yet there’s no way to track who’s who or what’s what when using pronouns.

A Better Approach

The ironic thing about robust process design is that mistakes like these are so commonly made because of the omnipresent urgency in growth companies today. Taking a more considered approach feels like it will take too long.

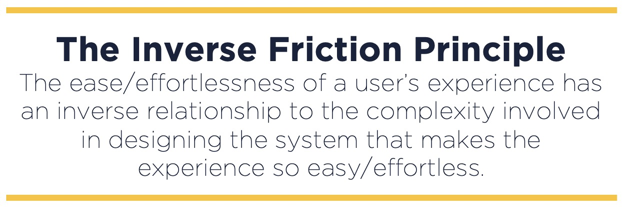

This is why we coined The Inverse Friction Principle: the effortlessness of an experience has an inverse relationship to the effort that went into designing the experience.

Here’s a simple, five-step approach to ensuring a solid process improvement discipline:

1. Define the problem by writing a problem statement

This is the essential step. Abraham Lincoln said, “Give me six hours to chop down a tree, and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.”

When you’re trying to fix a problem, a good rule of thumb is to spend two-thirds of your time defining the problem. That prep work increases the probability of a successful fix--and in less time.

A clear statement of the problem is required to create alignment.

2. Map the solution

If you can’t make the process work on paper, you’re not going to be able to make it work in real life.

Mapping the solution creates two benefits. The first is that it forces you to think through the solution in its entirety and then test for alignment to the problem statement. Second, you’ll also see other areas likely to be impacted by the approach you’ll be implementing.

When you skip this step (and it’s soooooo easy to skip), you’ll only find the problem with the implementation when you’re in the middle of it or after implementation, which will create a cascading series of negative implications.

The second benefit is that you make documentation a natural part of your process improvement efforts.

3. Review

Test the solution before implementing it. Another advantage of mapping the solution (step 2) is that it makes testing easier and faster. We’re often able to test the solution before we begin building by doing what we call a “paper test.”

The paper test typically involves two people. One person states each step in the process and the other person considers how it’s implemented and where things may break down. In my experience, we identify a conflict about half of the time. Identifying the problem before it’s built & implemented makes it a whole lot easier to fix.

4. Build

We build out the solution and add documentation to the appropriate playbooks and/or operations manuals.

5. Implement

Launch it.

I remember when we started to implement this approach here. My head of operations, Jess Cardenas, was highly skeptical. We were amid several complex implementations, and the team was at full capacity (maybe even over capacity).

I’m paraphrasing here, but when I finished walking through this approach, she replied, “This is all a great approach, and I think we should do it; I just don’t think we can do it now. We’re already falling behind, and we just don’t have the time.”

The irony is that one of the leading causes of our lack of capacity was the time spent fixing things after they were built. So we agreed to try it for two weeks and, if we were in a bind, to just do step 2 (map it). Of course, I knew that by mapping, the problem would have to be defined.

We never had to discuss it again.

Within a month, our capacity problem was gone, and our clients were happier than ever.

Doug Davidoff

Doug Davidoff